It’s time for me to answer another set of frequently asked questions, one that I get almost weekly so I need to make a blog post about it. Do you use GND filters, how do you choose the right filter, which ones should I buy, how do you position them, and how do you meter for them? Well the answer to the first question is a big definite yes, I use GND filters for the majority of my images and I will explain the rest throughout this post in great detail.

Make sure to read my last blog post - Metering and Exposing Color FIlm - as these two go hand in hand and build upon each other. The goal of this article is to dive deeper into the topic of GND filters.

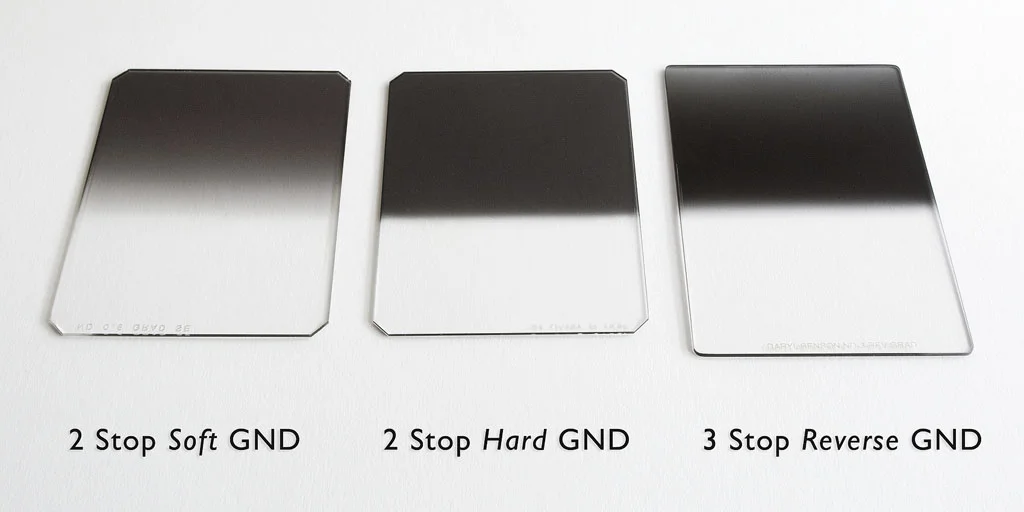

Just to cover the basics, GND is short for Graduated Neutral Density filter. These filters have a color-neutral area of density at the top of the filter used to darken skies and then gradually become clear towards the bottom of the filter. Density refers to part of the filter that allows less light through and they are measured in how many stops of light they darken the exposure by. They are available in different levels of density that darken exposure by one to four stops of light. They also come with a hard or soft edge, referring to how abrupt the transition is from dark to clear. When you see them for sale you will often see numbers like 0.3 or 0.6 associated with a SE for soft edge or HE for hard edge. 0.3 means it darkens the exposure by one stop, 0.6 by two stops and so on.

Image showing soft edge, hard edge, and reverse GND filters

Since I use film for all of my landscapes, I find these filters to be critical for countless situations. I would guess I use some sort of GND filter for nearly 75% of my images and just about every grand scenic that includes sky during golden hour or sunset. My goal is to get the image right in one exposure, and using film I don’t want to mess around with bracketing and blending images on the computer later. Many digital photographers may prefer to do this in Photoshop and I understand because you have more flexibility than with a filter, but many using digital may also prefer to try a GND filter so they can get it a lot closer with the first exposure. This article is aimed to help film or digital users as the methods are the same.

What brand filters should I buy?

For some reason this is probably the question I get most frequently so I guess I’ll cover it first. People often obsess about brand names and rattle off four different brands in an email they send me about filters. Or any email I receive on any topic, people often have some oddly strong association with various brands for products of all types and I’m not one to care so much as long as the tool gets the job done. That said, there are a lot of good brands of filters available but I will give you some warning about the Cokin filters. The Cokin filters are not color neutral by any means, in fact if you look at the name of their graduated filters they call them “gradual grey” so they don’t make any claims to be neutral. They do however attract a lot of beginners because of their low price point, which is understandable. If you’re using digital you may be able to get away with them because you can correct the colors, but on slide film you’re going to have the wonkiest skies with crazy purple hues. If you happen to use a polarizer with one of these filters you’re probably going to get waves or rainbow colors like looking through low quality car window tint through polarized sunglasses. These filters are cheap, but probably not worth spending your money on. If you’re on a really tight budget (hey, we’ve all been there) then I can say they make reasonable color filters for black and white film.

My camera shown with a 2 stop soft GND filter in a Cokin "P" size holder attached to the lens

As far as the rest of the brands go, it’s really up to how deep your pockets are. I’ve always been a fan of not spending more money than necessary so when I saw the Hitech (now branded as Formatt Hitech) filters they seemed like a great deal and they are. True neutral density, they make a size that fits right into the Cokin “P” holder (which saves you a ton of money), and they seem to be great quality to me. I travel to deserts and sandy places a lot and eventually you’re going to get sand in your filter bag. It’s just going to happen, no way around it. Sand will eventually destroy any brand of resin filters so I consider my filters to be a wear item that need replacing every few years. I would rather destroy less expensive filters but maybe that’s just me. These filters can generally be found for about $30 each from Adorama or B&H. If you’re gentle on camera gear (not like me!) you could consider glass ones which are far more scratch resistant but can be shattered.

The other brands like Lee, Singh-Ray and probably some others that have popped up on the market all make excellent products as well but you better have deep pockets especially if your lenses require large filter sizes. I have a Singh-Ray reverse GND filter that I use for special occasions which I’ll cover later. I needed it for special scenes so I had to pony up the cash. Go with the brand that feels best to you. If you’re the type that worries your images will be sub-par when you use less expensive brands then go all out, I dare you. If it means anything, 95% of my GND usage is with the Hitech filters but I’ll let you be the judge.

A 1 stop soft GND filter was used to balance the exposure in this reflection scene with soft light. Velvia 100 4x5, 135mm lens, 1/4 second at f16.

Whichever brand you decide to go with, make sure to think about the largest size filter you could possibly need for you widest and biggest lens. This will be the size you have to go with for all your filters. I’ve been fairly lucky shooting 4x5 as the largest front lens threads I have are 67mm. This allowed me to get away with a cokin P size system which saves a ton of cash and a ton of space in the camera bag. My widest lens (75mm) showed a tad of vignetting from the filter holder so I ground off the third filter slot and used two tiny screws and a rubber band to hold the device closer to the lens which mitigated the problem. I also made a similar modification to the filter holder for my panoramic camera. Sounds ghetto, but I’m all for making things work and it doesn’t hold me back one bit in the field.

If you’re shooting a system with large and/or wide lenses (over 77mm filter threads and wider than ~21mm equivalent), you’re probably going to have to go with a bigger system. This is very often the case with full frame DSLRs or modern 35mm film cameras that have wide lenses with huge front elements. Make sure to do your research here first as you definitely do not want to buy a filter system twice!

Which type of GND filters should I buy?

This is probably a far more important question. My most used of all my filters is the 2 stop soft GND filter. This filter is where it’s at! If you meter enough scenes you’ll notice that very often during golden hour side light and front light, the sky is just about exactly 2 stops brighter than the foreground. This seems to be the case for a wide variety of landscapes like the mountains or the plains where the foreground is a middle tone like grass or trees. The benefit of the soft edge allows you to place it over the sky when it isn’t a perfectly flat surface like the great plains, so if there’s a mountain or tree in the photo it won’t be completely darkened they way it would be with a hard edged filter.

"Fern Creek Sunrise" - An image showing a common use for a 2 stop soft GND filter during sunrise. Provia 100f 4x5, 75mm lens, 4 seconds at f22 with two stop GND and dodging with darkslide in the center of the valley.

When you’re shooting in the desert with light-colored rocks in all directions you might find that the ground isn’t much darker than the sky, perhaps only one stop or even the same exposure. I find myself using a one stop soft filter for these occasions but that’s because I use slide film often and the exposure needs to be perfect. If you’re not using slide film on a regular basis or if you’re shooting digital, I probably wouldn’t bother with one of these because you can easily correct for one stop of exposure variation in post.

"Horizon" - Example where a one stop GND filter subtly darkened the sky to work with the water. Provia 100f 6x17, 105mm lens, 30 seconds at f45 with center spot ND filter and 1 stop GND.

If you’re going to shoot scenes where you have very hard and flat horizon, such as when you’re standing at the top of the Grand Canyon or if you’re on the plains, you might want to invest in a hard-edged filter. I’ll be honest, I don’t use mine often even when shooting on the plains. They are very tricky to place and you absolutely have to make sure that you stop down your lens when checking placement. I will cover GND placement in detail later.

A rather unique kind of filter that I use when shooting into the sun over flat horizons is a reverse GND filter. These filters are clear at the bottom with a rather hard transition to the darkest point in the middle, then they gradually get less dense towards to top. This accounts for the area just above the horizon at sunset/sunrise that is the brightest as you look into the sun and allows the darker areas in the sky above the horizon to be exposed correctly. I’ve found the 3 stop reverse filter to be perfect for my uses and is the only one that I have purchased. The image below is a good example of when to use it.

"South Platte Valley Sunrise" - The three stop GND filter worked perfectly here, darkening the horizon the most while maintaining proper brightness higher up in the sky. Ektar 100 4x5, 135mm Lens, 1 second at f22, 3 stop reverse GND filter.

Placing the filters perfectly

This is one of the GND filter topics I get the most questions about and is crucial to getting the image exposed correctly. Nothing will ruin an image quicker than a sloppily placed GND filter, but don't worry there's not that much to it! The key thing to remember is to stop the lens down before you place the filter. SLR cameras should have a depth of field preview button to accomplish this, but on my large format lenses I just move the aperture lever to the desired setting that I will use to take the photo. This is incredibly important when using GND filters that have hard edges, as the transitioning edge will not appear in the same spot when the lens is wide open versus stopped down.

Sometimes it still isn't easy to see where the filter has been placed. If you have any uncertainty about how accurately you have placed the filter, I would lean towards placing it lower than the horizon rather than above it. If you place it too high you'll have a light band in the sky just above the horizon that is very obvious and very hard to fix later on. Over-darkening just a tad of the ground below the horizon usually doesn't hurt much and almost appears more natural but try your best to place it precisely.

Example showing different filter placements. In this scene, the dark line on the horizon was a field of alfalfa beyond the wheat. In deep red sunset light the green alfalfa will always appear to be nearly black so I didn't concern myself with the exposure of that area as it became a natural border between the ground and sky, just the sky and the flowing wheat field were important.

Tip for large format photographers: Yes, I know you won't be able to see a darn thing on the ground glass once you stop the lens down to f32. It's just one more thing we have to deal with. Make sure to use your dark cloth and just look carefully at the horizon where you want to place the filter as you move it up and down. I find myself sliding the filter up and down in the holder several times before finding the exact spot where I want it, letting my eyes adjust to the very dark image on the ground glass. You probably won't be able to make out subjects in this light, but just focus on the shapes and you should be able to make it work. If you're having trouble with the scene I would recommend using a soft edge filter and some educated guesswork, aiming for lower in the image rather than high. A misplaced hard edge filter will most certainly ruin an image so don't use them unless you're sure of your placement. I had to really scour through my images looking for an time where I used a hard edged filter, the sample of the wheat field above is one of only two I could find which goes to show how rarely I use them.

Aside from your filter choice, there are two more factors that determine how hard or gradual the transition from light to dark will be: your lens focal length and your aperture. A longer focal length will make the transition smoother just as a more open aperture will as well. If you're using a hard GND on a wide 16mm lens stopped down to f22, you can bet that transition line would be about as hard as possible and show up blatantly in any image. Conversely, if you are using a 200mm telephoto lens at a rather wide aperture like f8 the filter will hardly show up because that transition area will be so far out of focus. For this reason, when using standard and longer lenses you may want to consider using a harder-edged filter as a soft 2 stop might not even show up well.

"Teton Fence Sunset" - Ektar 100 4x5, 135mm lens, 1 second at f32, 3 stop reverse GND filter

In the image above I used a 135mm lens (equivalent to about 40mm on a full frame camera) which is longer than most of my wide scenes where I use a 90mm lens. I was able to use my reverse 3 stop GND which has a fairly hard transition at the bottom because it appear softer with the longer focal length. Even still, you can see I placed the bottom edge of the transition zone slightly below the area I wanted darkened the most. The valley in the distance was already in shade so it should appear that way, then the filter softly darkened the mountains and the most dense area of the filter was over the sun and the band of sky directly above the mountains. This filter probably wouldn't have worked so well on a wider lens and this scene, the mountains would have likely been darkened too much. I should also note that the atmosphere had very unique conditions on this day with distant wildfires causing a haze to the air that softened contrast in the distant mountain range and made shooting into the sun even more favorable.

"Crestone Needle Sunrise" - Ektar 100 4x5, 75mm lens, 4 seconds at f32, 2 stop soft GND filter.

As far as soft filters go, placement is a lot less critical but still important. Again, it definitely depends on how wide a lens you're using and what aperture you want to shoot at so make sure to stop your lens down before checking placement. Remember with these filters that the transition is very gradual, so you need to think about the area that you need to control the exposure the most. In the above example it was most important that the bright sunlit mountain be kept in check with the rest of the scene so the darkest part of the filter needs to be over the peak. Since the transition is so gradual you will need to put the bottom edge of the filter area quite a ways lower to ensure the most dense area is where you want it.

What if you can't look through the lens?

Well, shoot. That's unfortunate. But don't worry I share your pain! I also use two camera systems that don't allow for viewing through the actual lens. This is a common problem for people using rangefinders or other unusual cameras like the Fuji 6x17 that I use for some panoramas. These cameras have a separate viewing apparatus that doesn't go through the lens you use for shooting, so there's really no way to precisely place your filter.

Ok, well there is. Some people have filter holders with measurements on them, then they go through the time to shoot several test rolls of white walls and see the results from every one of their filters placed at several different areas and at different f-stops. I will never do this in my life, so I have boiled the whole thing down to guesswork.

"Oh-Be-Joyful Peak" - Provia 100f, Mamiya 6, 50mm lens, 1/4 second at f16, 2 stop soft GND filter

First of all, if you can't actually look through the lens you're probably not ever going to use a hard edged filter on that camera. The two stop soft GND will be your friend. What I do is look through the viewfinder and see which area needs the most exposure control, thinking about how far approximately it is down into the frame. Is it in the middle? Top third? etc... Then I place the filter into the holder and slide it down to where the transition line on the soft filter is just below that part of the lens. If my bright area took up the upper half of the frame I would slide the filter just over halfway down the front of the lens, leaving the bottom third of the lens with only completely clear filter in front of it.

"Sneffels Range Autumn" - Provia 100f 6x17, 105mm lens, 1/2 second at f22, center spot ND and 1 stop soft GND filters. The center spot filter is for dealing with lens vignette on this very wide format.

This method of educated guesswork has actually turned out quite well for me and I have used it countless times. On the panoramic camera I mostly stick to the one and two stop soft filters and just slide them a good ways down the lens, usually placing the dense part of the filter over the top two-thirds of the lens. I try to avoid scenes with extreme contrast, and shooting into the sun over a flat surface would be very tricky with this system. Don't be afraid to try using GND filters one these types of cameras, it really isn't that hard.

Choosing the right filter for the scene

Having a fancy set of filters won’t do you any good if you don’t know which ones to use and when, so it’s important to choose the right filter. I’m going to go over some common scenarios where I use GND filters with some photo examples.

It's key to keep the scene looking natural, choosing the wrong filter will often result in a garish display that is obviously unreal. It's important not to over-darken skies or make images where reflections are brighter than the mountains. Most the time two stops is about the most you can get away with while keeping a natural appearance but read on for some other considerations.

Golden hour with side light:

"Upper Macey Lake Sunrise" - Velvia 50 4x5, 75mm lens, 1 second at f22, 2 stop soft GND filter

This is a very common type of scene and is typically where the 2 stop soft GND filter shines. Whether you're in the mountains or on flat lands with subjects protruding into the horizon, the soft 2 stop is usually just the right strength to sufficiently control the sky's exposure while not over-darkening subjects that stick above the filter edge. This is by far my most used filter, time and time again I meter a scene and find that this is exactly what it needs for proper exposure. In the scene above I would have placed the bottom of the filter transition right around the green bush in the water, this way the bright rocks, peaks, and the sky all get the more dense parts of the filter.

"Kebler Pass" - Velvia 100 4x5, 135mm lens, 2 seconds at f22, polarizer and two stop soft GND filter

Here's another example of some golden hour light and again I used the 2 stop soft GND filter. I would have placed the bottom of the gradient in about the center of the image, so that it reaches its full density at the tops of the peaks and the bright sky. This was again with the longer 135mm lens so the transition is going to be very smooth and it would be hard to notice a filter was even used which is always my goal. Bad filter usage can look just like bad HDR images. I've also had people ask me about using GND filters with polarizers and the answer is that yes you definitely can. Just make sure it's not a really cheap GND filter like a Cokin one, as I mentioned earlier you will get bizarre rainbow effects with that combination.

Sunset/Sunrise facing away from the sun:

"Primrose Bloom and Stormy Sunset" - Velvia 50 4x5, 90mm Lens, 8 second at f32, 2 stop hard GND filter

This is another great time to pull out the filter kit, also most likely the 2 stop soft. In the above image I actually used a hard edge filter because the landscape was so flat and I wanted the earth's shadow to appear a deep purple/blue hue as it does to they eye, but if there had been anything sticking up into the horizon I would have used a soft filter. Again, filter placement is critical with the hard filter, so stop the lens down and place it just barely below the horizon so the strongest part of the filter starts at the sky.

"Pawnee Buttes Sunset" - Velvia 50 4x5, 75mm lens, 2 seconds at f32, 1 stop soft GND filter.

The above image is one of those rare times where a 1 stop filter comes in handy. You may find in rather light toned terrain (like this area of exposed prairie earth) that there isn't much of an exposure difference between the sky and ground. Because I'm using a very low dynamic range film like Velvia I wanted to make sure it was perfect so I still used a filter. If you're using digital you could likely get away with no filter for this, and if all you had was a 2 stop filter that probably would have worked fine no matter what format you're using. As a note, it's rather hard to mess up filter placement on a 1 stop soft filter. The change can be hard to see in the viewfinder, so if you're having trouble just place it towards the center of the lens depending of course where you have the horizon in the frame.

Facing towards the sun at sunrise/sunset:

"Prairie Tree Sunrise" - Provia 100f 6x17, 105mm lens, 2 seconds at f32, 3 stop reverse GND and center spot ND filters.

Backlit sunsets is where the 3 stop reverse GND really gets handy. The sky above a middle-toned horizon is often about 4 to 5 stops brighter than the ground, but keep in mind that you want bright sky in a sunrise to appear bright so you don't want to make it exactly even with the ground. If you put the strongest part of a 3 stop reverse GND filter over the area over the horizon then you will have a sky that is one to two stops brighter than the ground which is perfect for a luminous feeling to the image. The filter then loses density towards the top which helps prevent the over-darkening higher up in the sky. Notice this image was taken with the panoramic camera which does not let me look through the lens to preview filter placement. That means this was some guesswork, but I do remember bracketing a couple different filter placements over two shots due of the likely chance that one of them would have the filter in the wrong location. Good thing I did because the other exposure was toast.

"Winters Warm Glow" - Velvia 50 4x5, 75mm lens, 2 seconds at f22, 1 stop soft GND filter

The above is a rather unusual lighting situation but I was still shooting into the sun at sunrise so I'm going to put it here as a lesson to always use your meter to determine the correct filter and not some set rules you learned from a blog post. The snow was bright and catching sunlight, but the sun itself was quite filtered through a layer of blowing snow that softened contrast greatly like a giant softbox. Usually I would expect to use a three stop reverse filter here but I was surprised when I check with my meter and saw only two stops of difference between the snowy ground and the sky. The sun was of course several stops brighter but the haze of the blowing snow in the sky kept it from being one blown-out orb and also refracted light into the warm colors of the spectrum. To keep the sky appropriately bright I used just a 1 stop soft GND filter to balance exposure, placing it just below the center of the image.

It was risky using a filter at all in this situation. If you're going to place a filter between your camera and the sun, you better make sure it's clean and free of scratches as well as perfectly parallel with the surface of the lens. Placing a piece of dirty resin plastic in front of the lens is a great way to increase unwanted lens flare. Having the sun dead-center in the frame helped as flare is less likely to appear, I also looked through the ground glass to verify that no flare is visible.

Balancing water reflections and sky:

A water reflection will almost certainly always be darker than the object being reflected, and again it's typically by two stops. This is a common scenario for mountain lakes at sunrise where you have a bright sunlit peak above an alpine pond in the shade. I have never yet encountered a reflection that is three stops darker, so make sure not to be tempted to pull that filter out as your reflection will end up brighter than your mountains which would be obviously tainted to the eye.

"Notchtop Alpenglow" - Ektar 100 4x5, 75mm lens, 6 seconds at f22, 2 stop soft GND filter

The above is a classic example of that type of scene. A peak and the sky get bathed in the first light of day, the water below has a darker reflection nearly matching the tones of the grasses and rocks of the shore. For the most part that makes these scenes rather easy to expose, just place your 2 stop soft GND at the bottom of the peak and you're set. Meter for the water reflection and expose.

Special circumstances:

There are some times where GND filter usage can be tricky at best and some other ways to use them, so I'm going to cover a couple scenarios here.

"Fall Storms over Bear Lake" - Ektar 100 4x5, 90mm lens, 1 second at f22, 1 stop soft GND filter.

In the above image we have a very bright stormy sky being lit by morning sun, as well as blazing autumn aspen basking in that same light. The aspen reach up into the top of the image but the sky itself is a bit unreasonably bright. First of all, it might be a good idea to use a film type that can handle this situation but of course some of us use rolls and don't have the luxury of changing film with each shot. In a scene like this you need to come to terms with what the tones will look like, realizing that brightest part of the sky will likely be nearly pure white. That's ok sometimes, just make sure the rest of the important stuff falls into a range where it will expose properly. Since there are trees sticking way up into the sky you can't get away with even a 2 stop filter as they will be darkened noticeably. For this scene I just went with a 1 stop soft GND and slid it about halfway down the frame, carefully metering everything else setting the sunlit trees as my most important detail. They should appear bright so I went with about 2/3 of a stop overexposure on the leaves and everything else fell into place.

In many situations like this I would even consider using the corner of my film darkslide (you can use any black object like a glove or cloth) to dodge the middle area in the sky. Dodging that area for half the exposure time will give you an additional one stop of darkening and you can do it in the shape of a mountain valley, as GND filters do not come in such shapes. If I recall correctly, this morning had rain and too many other factors going on to allow me to do this but it's a great trick. I outline this in greater detail in my last blog post here.

"Windmill on Fire" - Velvia 50 4x5, 90mm lens, 4 seconds at f22, 1 stop soft GND filter used upside down.

Here's an example of a rather unusual use for a GND but there are a lot of ways to get creative with them. In this image above I wanted the windmill and ground to be silhouetted which wasn't a concern because the sky was far brighter, however the sky was significantly brighter towards the horizon compared to higher up and I was using a wide lens. My solution was to put a 1 stop soft filter upside down and darken the lower part of the sky to bring it closer to the top in exposure. This is a bit of a backwards idea but it definitely helped when using a sensitive film like Velvia. You might even find forest or waterfall scenes where a soft one stop gradient across the image might help, be it from the top, bottom or even sides. Get creative and always think about ways to use these tools.

Metering with GND filters

This is of course just about the most important aspect of using GND filters, so why have I done all this talking and not mentioned it? It just just happens that I covered this topic extensively in my last blog post on Metering and Exposing Color Film so make sure to check it out by clicking here.

GND filters are a very integral part of my metering process so that's why it's in the last post, but to give you the quick run-down I will copy my process here:

Average meter the foreground (the part that will not be darkened by a filter).

Set the camera's exposure to that setting.

Average meter the sky, calculating how many stops brighter it is compared to the foreground. Photography is all simple math. Each stop brighter is one half the shutter speed. For example, if the foreground meters 1 second at f32, one stop brighter would be 1/2 second at f32. Two stops brighter would be 1/4th second at f32, and three stops brighter would be 1/8th second at f32.

Decide on a GND filter based on that calculation and how bright you want the sky to appear.

Place the GND filter on the lens, making sure to stop down the aperture before you place the filter. This increases the depth of field and makes the transition edge of the filter more accurate.

Take the photo using the settings from step 2.

If there's any questions, make sure to refer to that blog post, I really hash out all the details about my entire metering process.

I believe that covers everything I need to mention about GND filters. If you have any questions or thoughts please leave a comment below!

Did you enjoy this blog post? Feel free to make a small donation. By clicking the button below, you can give me a $5 donation easily through PayPal (no account needed) that helps me greatly. Every sheet of my large format film costs about $5 so your donation can keep me out there photographing the beautiful landscape!

Better yet, pick up a copy of my brand new ebook: "Film in a Digital Age"