This one is for you DSLR scanning folks, or those who want more control out of your film scanner. It’s been just about three years now that I’ve been using a drum scanner which has drastically changed my scanning process with color negative film. While the software for this scanner is incredibly powerful, it falls apart when it comes to inverting color negatives. This means that I had to develop a method to do this on my own that can work for every image I throw at it. While I love sharing my findings with the film community, I wasn’t sure that a technique I developed for drum scanning would be helpful to the average shooter. It turns out that this manual inversion can work no matter what you use to scan your film with.

I want to start by mentioning that there certainly are some software options for people looking for automated color inversions. Two main choices are Negative Lab Pro (Lightroom Plugin) and ColorPerfect, a Photoshop Plugin. The former of those two has become quite popular lately and seems to be a great option for many people, however for my drum scans that push 2GB in size Lightroom isn’t all that wonderful for me. While both of those plugins work well for a good number of daylight or normal image exposures, they can struggle when it comes to pulling delicate sunrise/sunset hues out of the highlights in negative film. Rather than looking for the one-click option, I wanted to dive deeper and crack the magic secrets of color negatives. It turns out that doing it manually does not take very long at all and provides you with a level of control and knowledge that helps you understand the process.

At the end of this article you can find a video screen capture of my editing process, to help illustrate how quick and easy this really is. Update December 2020: there is a second video of a night time scene with a more challenging white balance, see both at the end of this post.

First off, we need to make a scan of the negative. We will be scanning the negative as is, in all of it’s weird orange-brown glory. You can do this with whatever scanner or DSLR you might have, I made sure to test this method using both options. The goal here is to make a scan with no adjustments applied to it, we will be doing everything manually in Photoshop. Let’s start with the settings I used in Epson Scan since that is the scanner software I have.

Settings used to create a positive scan of a negative in Epson Scan

This is rather straightforward, we just want to make it so the scanner does no (or as little as possible) in the way of color corrections. We will set the Film Type to “Positive Film” which will make it so the software does not try to invert the negative, then we need to go into the Configuration window under the Color tab and click on the “No Color Correction” button. See the check marks in the above image for reference. Go ahead and make the scan, it should end up looking exactly like we see in the preview window of Epson Scan. If you are using a different scanning software the idea is the same; we want to scan as a positive and turn off any software color or exposure corrections. Notice that in the scan I have included a portion of the film border. This is important and will be used later on. Try to position your film inside the scanner holders so that you have a bit of border (or the space between frames on roll film) showing.

For those who are using a DSLR to scan their negatives the idea is pretty much the same. We need to make a basic exposure of the negative with no clipped highlights or shadows. I used the same holder that came with my Epson v700 to hold the film over a color-corrected light table that I have. I then set the camera to daylight white balance and took an exposure. You will definitely not want to use auto white balance as the negative will confuse it to no end. I found that the meter on the camera was thrown off by the negative and I had to set the exposure compensation to -1 stop. I just used my little Olympus m43 camera that I use for a light meter to do this test and just took the shot handheld. If you’re planning on doing DSLR scanning you will want to get a tripod set up and some sort of consistent method so that you can get uniform results. You’ll also probably get some exposure settings dialed in over time that will work for all your film scanning.

Comparison of negative film scans made using the Epson v700 and a mirrorless camera

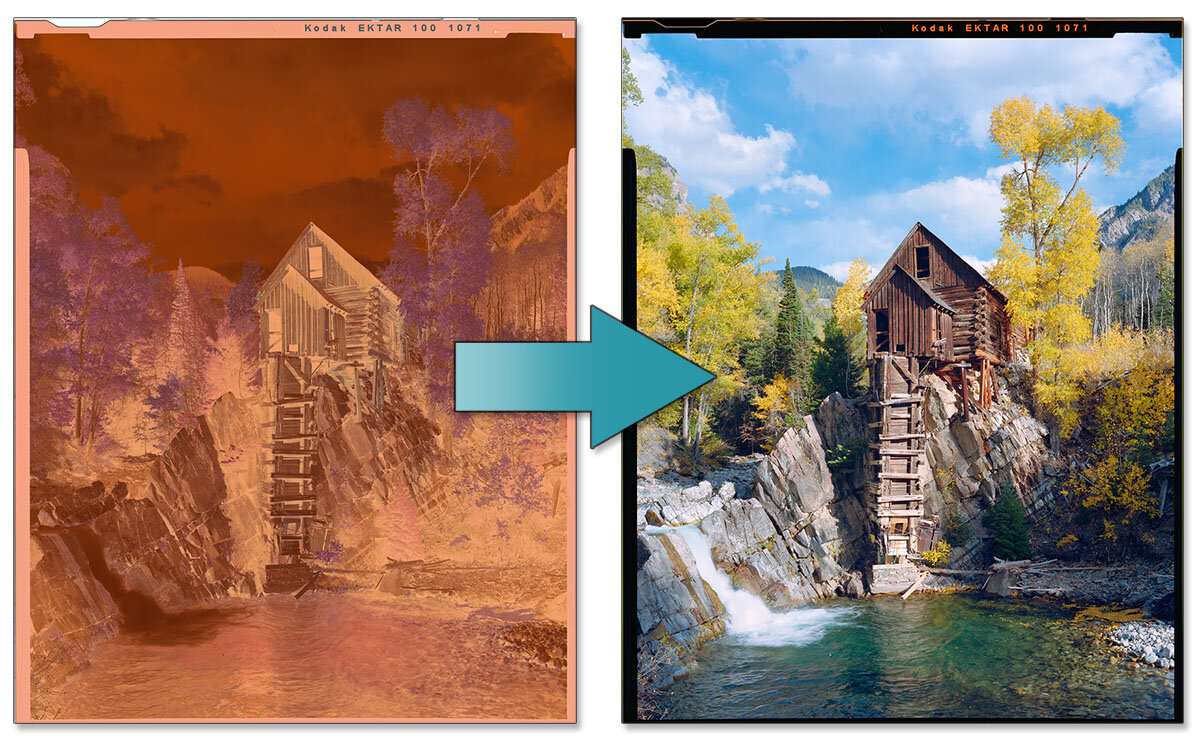

Above you can see the “raw” scans that came out of both my Epson and the mirrorless camera. This is what your file should look like roughly, more than anything it should resemble the film itself closely. In a perfect world, you could even shoot color charts and build profiles to make your digital camera or scanner “calibrated” but it’s ok if you haven’t. Most of the film inversion is going to be up to interpretation either way. Every device is going to make a bit of a different looking scan depending on the make and model; notice that the Olympus appears to have made a more saturated brown which will affect our inversion. Oversaturation is probably rather common in a lot of digital cameras, but I wouldn’t fiddle with the colors of the negative shot at this point. Remember that out of these messes of color we will get vibrant greens, autumn yellows, and blue skies. That comes next.

Moving forward for this post I will use the Olympus scan as I assume these days even more people will be using digital cameras than actual scanners to digitize their film. At the end of the article I will supply small PSD files with all the layers intact for both the Epson and the Olympus scans so you can see how similar the two are yet also the minor differences. The first thing we must do is a rough inversion of the negative, which I do by simply making a curves layer and dragging the shadow point to the top and the highlight point to the bottom.

Making the initial inversion

The image has now been inverted, but is very cyan and bright. Next we will use the film border as a shadow point that will also reduce some of the film base color cast. Use the eyedropper tool (press the I key) and set it on 5x5 pixel average. Make sure it is set to “All Layers” under the Sample menu and that you are currently on the background layer, not the curves layer we just made to invert. Click somewhere on the film border to make that your current foreground color. Due to the Epson film holder I used, the actual film border is just that little sliver in the top of the image that is darker than the rest, everything beyond that is the actual film holder. It is much easier to select the film border on roll film where you have the space between each frame, or on a drum scan where I scan to the edges of the film. The eyedropper tool should show something of a middle cyan color, like you see in the example here.

We then will make a new fill layer with this color. I’m a big fan of keyboard shortcuts to make this process quick and painless, so hit Ctrl+Shift+N to make a new layer and press enter. For you Mac fans out there, everytime I say Ctrl, you will probably need to press the Command key instead. Now we want to fill that layer with the color we have selected. Press Shift+Backspace to open the fill box, select “Foreground Color” under the dropdown menu for Use and press enter. Your whole screen has now gone cyan in color. On the layers panel, use the drop down menu for this layer and change the blending mode to “Subtract.” You have now essentially subtracted the film base from the image and set that as pure black. Any shadows in your image are no longer a medium cyan but instead very close to a neutral black. I find that this layer clips the shadows a tad more than I like so I set the opacity of this layer to 80%.

The image should now look like what you see on the right above. If not, make sure your layers are in the correct order. Ok, we’re still looking at a muddy mess here but you’ll be amazed by what the next curves layer will do. Make a new curves adjustment layer. We will now set the overall white point and correct most of the colors in just a single layer. Go into the red color channel and drag the highlight point over to the left while holding the ALT key. Holding ALT makes the image go black and then allows you to see when that channel will start to clip as you drag the point over. Once you see some clipping, back off a little bit. Repeat this process with all three color channels.

After you do this in all three channels you have effectively set the white point of the image. Since this is a daylight scene we know that the puffy white clouds should be white which makes things easy.

You’ll probably notice that now the image is far too bright, so we’ll head back into the RGB channel of the curves layer and bring down the curve significantly. We will also go into each color channel and adjust the colors. On nearly every negative I’ve worked with, blue needs to be reduced significantly, green by a good bit, and red by either just a tiny bit or not at all. Below are the curves as they were adjusted for this image.

You can notice now that we are really making progress. The white point and shadow points have been set so now it’s time for minor tweaking. The Olympus seemed to oversaturate the negative, which in the inversion resulted in a cyan sky color that just doesn’t look natural. This can sometimes happen with other capture devices but the fix is easy. We’ll make a Hue/Saturation layer and shift the cyan a tad towards blue, lower the saturation, and increase the lightness. Sometimes I will also do this to the blues but to a lesser extent.

Finally I just want to work with one more layer to tweak the contrast a bit. This is a simple curves layer where I will more carefully set the highlight point in the RGB channel and add some contrast using a gentle S curve.

At this point it’s up to the photographer to decide where to take the image. If you wanted to fine-tune things a little more this would be a good time to add some luminosity masks. Negatives can have endless interpretation but this inversion process will give you a great starting point every time.

What about those scenes where you don’t have puffy white daytime clouds to judge the white balance? Sunrise, sunset, twilight, and unusual light are the bane of every scanner software or inversion plugin out there. It’s a challenge to deal with no matter what and is one of the reasons why it’s not always a great idea to go months or years between the time that you shot the negative and the time when you finally get around to scanning it. Your memory of the scene and light will be a big part of what you have to go off of.

What you see in the image above takes care of the issue nearly every time for me and is one of the big benefits of manual inversion. You get to watch what each color channel is doing as you adjust the curves layer. In the image above I was high up in the mountains at twilight, just as the earth’s shadow was starting to rise into view with the vibrant Belt of Venus above it. At this altitude and under such clear skies, the colors were quite magenta and strong. Setting anything as a white point would not make this image work at all. Typically all that is needed is to just not come over as far when setting the green highlight point, which results in the image appearing more red/magenta. Of course you’ll notice that you can go quite crazy with this; it’s up to your best judgement to do it well, along with your memory of the scene and how you want to interpret the negative.

Watch the short video below to see my editing process on the image shown in this blog post. This is a simple screen capture and the first time I have done something like this, so please forgive any lack of quality in the video. The screen capture software doesn’t seem to show the cursor precisely where it was on the screen and it doesn’t show menus that I open, but it should be good enough to give you an idea.

I’ve also created a new video showing the process on a somewhat trickier night scene where the white balance isn’t so straightforward. You can watch that video here:

As promised, here are the two PSD files for both the Epson and Olympus scans. These two files will help you realize how similar the process is, but also show how each image capture device will vary and how you will have to tweak the curves for your scanning methods.

Thank you for reading! If you enjoyed this content, perhaps you might also like my ebook “Film in a Digital Age.” Its 180 pages packed with knowledge and dive deep into all sorts of topics to help you master your film technique.